Thursday July 29, 2021

In her lifetime, Sonoma County’s Shugri Salh has encountered many different worlds.

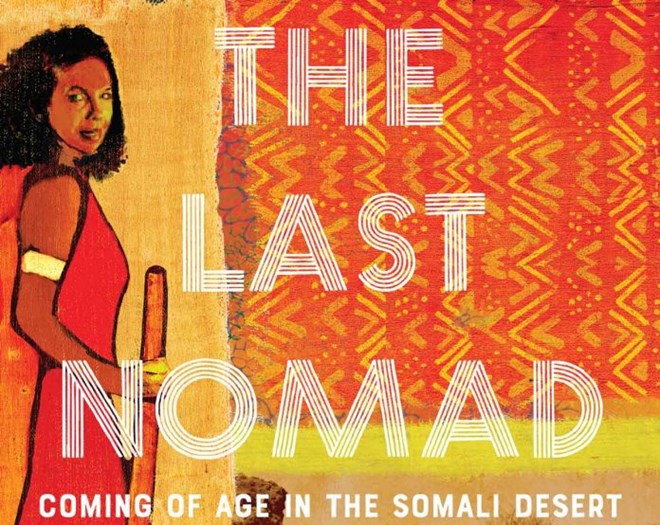

With an engaging wit, fierce feminism and vivid writing that catches readers instantly, her new memoir, The Last Nomad: Coming of Age in the Somali Desert, presents a rich portrayal of her indomitable spirit.

“I am the last nomad,” begins Salh’s memoir. “My ancestors traveled the East African desert in search of grazing land for their livestock, and the most precious resource of all—water. When they exhausted the land and the clouds disappeared from the horizon, their accumulated ancestral knowledge told them where to move next to find greener pastures. I am the last person in my direct line to have once lived like that.”

The book chronicles Salh’s extraordinary journey from a bucolic childhood with her nomadic grandmother in Somalia, to her experiences with and subsequent escape from her country’s violent civil war, to adjusting to entirely new homes in Canada and then California.

“How fitting that my story is coming out in a time of great division and hatred, especially toward immigrants and refugees in general,” Salh says. “I am a believer that stories have ways of connecting us and reminding us of our shared humanity. So by telling my story, I hope to remind us that we share humanity.”

The riveting and lyrical tale she tells is complex and reflects many angles of a patriarchal nomadic culture that is by turns oppressive and supportive, frightening and beautiful. She imparts these contradictions through the lens of her own experience living a double life in the city and villages and in the desert, and later in refugee camps and even a Kenyan jail.

Her storyteller’s voice infuses her memoir with a playful, poetic spirit in spite of the myriad hardships she describes, including the early death of her mother, her distant and abusive father with his multiple wives, having 22 siblings, desert predators, the accepted practice of female circumcision and the consequences of civil war.

“I had no other choice but to be brave,” Salh says in the book, and somehow she makes it all sound like an adventure—an example of her poet’s voice and her earned strength and resilience.

She remembers the desert as a dangerous place where drought, hunger and predators were a constant threat, even as she grew up dauntless and free, learning how to herd camels and raise her own goats, all the while becoming part of the community found through the courtship rituals, nightly stories and cooking songs passed down through generations of ancestors.

While she remembers nomadic life with much fondness, she is clear about how hard it was, and that it’s a way of life that became increasingly difficult to maintain as the outside world crushed in around it. Less territory, fewer natural resources and more interference from outside cultures and events ultimately made it impossible for her family to function in the same way it had for generations.

Salh is a modest person by nature, but is very open about her personal experience with her culture’s accepted practice of female circumcision. She speaks matter-of-factly about her community’s total belief in the practice. Even after undergoing the brutal ritual at age eight, she describes how she and the other circumcised girls felt sorry for the girls who weren’t. Once she grew older and moved away, she began to understand the practice as female genital mutilation. Sahl, however, accepts her body the way it is and feels whole unto herself.

“We must understand that what we go through in life is not in vain, that the lesson we learn from every hardship helps conquer the next challenge,” she says. “I hope my story ultimately inspires those who have faced adversity in their lives, and brings us all together as humans, regardless of our backgrounds, religion, nationality and gender.”

Born in 1974, the fourth daughter in a culture that didn’t value girls, Salh was shuttled from town to town during her youth, from family member to family member, landing in the desert with her nomadic family members, including her beloved ayeeyo—grandmother—at age six, and later finding herself in a Somalian orphanage.

Salh’s family structure was nontraditional, even for her culture, but provided her with strong women mentors nonetheless, including her ayeeyo, who did the work of both a man and a woman out in the desert. Another mentor was her teacher at the orphanage, Layla.

“Layla taught me that girls could be as strong and as important as boys,” she says in the book. “No one had ever told me that before. Layla taught me how to become the kind of woman I wanted to be. Strong and resilient.”

Salh indeed became strong and resilient, and her resilience is not hardness, but flexibility without a trace of bitterness for what she has experienced. “My inner strength comes from gratefulness,” she says.

She adds, “Honestly, when you are grateful you see life through a completely new lens. I look at the world as if it’s working with me instead of against me.”

She comes from a long line of storytellers, including her ayeeyo—creating a landscape with words, bringing the reader along with her, while infusing her younger self’s memories with her mature perspective.

“There is a saying in my culture that loosely translates: death is inevitable, so make sure your words prevail,” Salh says. “I realized that if I didn’t write this story of mine, it would die with me. It is not only my story, but the story of my family, nomadic culture, my country, and what it is like to be a Somali woman. It is important for me to record my unique upbringing, so my children and their descendants know the strong women they come from.”

And she’s not finished yet.

“Initially, the plan was to tell my story and be done, but something turned in me, and now I want to tell more stories, especially after talking to many Somali women,” she says. “Currently, I am working on children’s stories of nomadic life and putting the finishing touches on the young adult version of The Last Nomad.”